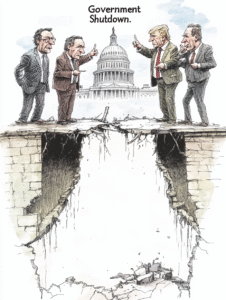

Let’s Start with the Obvious Question: Why Can’t They Pass the Bill?

If you’ve ever wondered why government shutdowns seem to happen over and over again, you’re not alone. Every year, as the September 30th deadline approaches, Washington drags out the same suspense: Will the government shut down?

And here’s the kicker — the answer usually depends less on money and more on math. Specifically, the kind of math only the Senate understands: 51 votes for a majority, but 60 votes to move anything forward.

That little gap — the one between 51 and 60 — is where the filibuster lives. And that’s where the minority party finds its leverage.

How a Funding Bill Is Supposed to Work

Let’s start with the version they teach in civics class.

- The President submits a budget proposal each spring.

- The House and Senate Appropriations Committees review it and break it into twelve separate funding bills — Defense, Agriculture, Transportation, Veterans Affairs, and so on.

- Each chamber debates and amends the bills, then votes.

- Both versions get reconciled, passed, and signed into law by October 1 — the start of the new fiscal year.

That’s the clean, ideal process. But if Congress can’t pass those bills (and these days, they rarely do), they use a Continuing Resolution to keep agencies open temporarily.

And if that fails, we hit the dreaded government shutdown.

Why the Minority Party Can Pull the Brakes

Here’s where the civics lesson gets interesting. The minority party shouldn’t have much power in theory. But in the Senate, they do — because of one procedural device: the filibuster.

A Quick History of the Filibuster

The filibuster wasn’t part of the Constitution. It started almost by accident in 1806, when the Senate dropped a rule that would have allowed a simple majority to cut off debate. That small change meant senators could, in theory, keep talking forever — preventing a vote.

Fast forward to 1917: tired of endless debate, the Senate adopted Rule XXII, which allowed a “cloture” vote to end the discussion. But it required two-thirds of the chamber. In 1975, that threshold dropped to three-fifths (60 votes) — where it stands today.

So, if you’re in the minority and you can rally at least 41 senators, you can block almost anything — including funding bills — unless the majority cuts a deal.

How the Filibuster Shapes a Shutdown

Let’s connect the dots.

In the House, a simple majority can pass a bill. But in the Senate, you need 60 votes to move past debate — and most years, neither party has 60.

So the minority can say, “We’ll block this funding bill unless our amendments are included.”

It’s leverage by design — the filibuster gives the minority party bargaining power. It was meant to protect deliberation and minority rights, ensuring the Senate didn’t become a steamroller for the majority.

But in today’s polarized environment, that safeguard has turned into a brake pedal pressed full-time.

What used to be a tool for debate is now a weapon for delay.

When the Filibuster Meets the Funding Bill

This is where government shutdowns are born.

- The majority drafts a funding bill reflecting its priorities.

- The minority objects, demanding unrelated policy riders be added.

- Negotiations stall.

- The clock ticks down.

- The funding expires.

And when it does, the party holding the filibuster card can say:

“We didn’t get what we wanted during the election, so now we’ll use the budget process to get it.”

It’s legislative hardball — and because the public rarely understands the mechanics, it gets framed as “Congress failed” instead of “The filibuster is being used as leverage.”

Why Ending the Filibuster Isn’t a Simple Fix

You might think, “Well, if the filibuster is the problem, just get rid of it.”

Many have tried.

But removing it creates a new issue: whiplash governance.

Without the filibuster, whichever party has 51 votes could pass sweeping laws — and the moment power flips, the next majority could undo them all.

The filibuster, for all its frustration, forces some negotiation. It’s an anchor in an age of political volatility — but one that’s often abused to stall everything, not just bad ideas.

So Congress ends up with the worst of both worlds: gridlock wrapped in procedural righteousness.

The Real Story Behind Every Shutdown

At its core, every modern government shutdown is a fight over leverage — not funding.

The minority party knows it can’t win through votes, so it wins through delay.

The majority party knows it can’t govern without compromise, so it plays the blame game.

And in between, federal workers, agencies, and citizens get caught in the crossfire.

The system works — just not for the people it’s supposed to serve.

Where Communication (and Common Sense) Broke Down

Here’s the truth nobody likes to admit: this isn’t just political — it’s cultural.

We’ve forgotten how to talk to each other.

Somewhere along the way, politics stopped being about policy and turned into performance. It’s no longer about ideas — it’s about identity.

We cheer for our party the way fans cheer for a football team, and we hope the “other side” fumbles, even if it means the whole country loses yardage.

That’s not democracy — that’s division.

Schadenfreude — taking pleasure in the other side’s failure — might feel satisfying for a moment, but it’s a terrible long-term strategy for a nation.

It breeds distrust, resentment, and apathy. And the filibuster? It’s just a mirror reflecting that dysfunction.

I’m Embarrassed for Both Sides

Honestly, I am.

As someone who spent decades in federal service, I’ve seen brilliant, dedicated people who genuinely care about the public good. But I’ve also seen how politics above progress grinds everything to dust.

Both parties have had their turn playing chicken with the system — and neither has much to show for it besides headlines and heartburn.

I wish I could say I have a plan to fix it, but I don’t. Not really.

Still, I saw something on social media that made surprising sense — a simple list of five ideas that, while imperfect, at least start the conversation about getting our government back on track.

Five Common-Sense Fixes (That Might Actually Work)

- Two-Term Limit — Across the Board.

If the President gets two terms, so should everyone else. Senator, Representative, or otherwise — two terms and you’re done. No career politicians, no lifetime incumbency. Public service shouldn’t be a pension plan. - One Item Per Bill.

No more legislative piggybacking. If the bill funds the VA, it funds only the VA. No buried favors, no hidden riders. Let lawmakers vote on issues, not packages. - No Taxpayer-Funded “Fact-Finding” Trips Abroad.

If you’re representing a small corner of South Dakota, there’s no reason to “study trade routes” in Amsterdam. Travel should serve your constituents, not your curiosity. - Remote Participation for Votes.

It’s 2025 — if businesses, universities, and entire governments can run via secure video conference, so can Congress. Less travel, more time doing the job. - Proof of Representation.

Every member should demonstrate that their vote aligns with the will of all their constituents, not just their party base. Represent everyone, not just the cheering section.

Final Reflection: Where Do We Go From Here?

I don’t pretend these ideas are a silver bullet. They won’t heal polarization overnight or erase the distrust baked into our politics.

But maybe — just maybe — they’d remind us that democracy was meant to be a partnership, not a performance.

When I look at how divided we’ve become, I can’t help but think of something simple:

If we can’t talk, we can’t govern.

Until we learn to listen again — really listen — every funding bill, every debate, every government shutdown will be another symptom of the same disease: a nation that’s forgotten we’re supposed to be on the same team.

And if there’s one thing we can agree on, it’s this — the way we’re doing it now isn’t working.